Macroeconomics examines the economy’s big picture, focusing on issues like GDP, inflation, and unemployment. This section introduces key concepts and economic goals, forming the foundation for AP Macroeconomics study guides.

1.1 What is Macroeconomics?

Macroeconomics is the study of the economy as a whole, focusing on broad issues like inflation, unemployment, and economic growth. It examines how societies allocate limited resources to meet unlimited wants, addressing national income, GDP, and price levels. Unlike microeconomics, which analyzes individual markets, macroeconomics provides a comprehensive view of the economy, helping policymakers make informed decisions to achieve economic goals such as full employment and stable prices.

1.2 Basic Economic Concepts

Basic economic concepts include utility, resources, and factors of production, which are land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship. These elements shape how societies allocate resources to meet demands. The circular flow model illustrates the flow of goods, services, and payments between households and firms. Key economic goals are growth and full employment. Marginal analysis, comparing benefits and costs, is crucial for decision-making. Understanding these concepts lays the groundwork for analyzing larger economic systems and policies in AP Macroeconomics.

1.3 Economic Goals

Economic goals focus on achieving growth, full employment, and price stability. Growth involves increasing output for better goods and services; Full employment ensures jobs for all willing workers, minimizing unemployment. Price stability avoids extreme inflation or deflation. Additionally, equitable distribution of income aims for fairness. These goals guide policy decisions and are central to macroeconomic analysis, helping evaluate economic performance and inform strategies for sustainable development in AP Macroeconomics studies.

1.4 Scarcity and Opportunity Cost

Scarcity refers to the fundamental economic problem of unlimited wants exceeding limited resources. Opportunity cost, a key concept, represents the value of the next best alternative foregone when making a choice. For instance, using resources to produce more cars means sacrificing the production of other goods. Understanding scarcity and opportunity cost is crucial in macroeconomics, as they underpin decision-making and resource allocation, guiding how societies choose to use their limited resources effectively.

1.5 Factors of Production

The factors of production are the resources used to create goods and services. They include land (natural resources), labor (human effort), capital (man-made resources like machinery), and entrepreneurship (the ability to organize resources to produce goods). These elements are essential for economic activity, enabling societies to produce and distribute goods efficiently. Understanding these factors is vital in macroeconomics, as they drive economic growth and development, shaping the overall performance of an economy.

Economic Indicators

Economic indicators like GDP, inflation rates, and unemployment rates measure economic performance. They help assess the economy’s health, guide policy decisions, and predict future trends.

2.1 GDP and National Income

GDP (Gross Domestic Product) measures the total value of final goods and services produced within a country’s borders over a specific period. National income refers to the total income earned by a nation’s citizens, including wages, rents, and profits. GDP can be calculated using the expenditure approach (C + I + G + X) or the income approach (summing up all incomes). These metrics are crucial for assessing economic performance, growth, and standards of living, making them central to AP Macroeconomics study guides.

2.2 Expenditure Approach

The expenditure approach calculates GDP by summing total spending on goods and services. It is expressed as GDP = C + I + G + X, where:

– C is consumer spending (household purchases),

– I is investment (business spending on capital goods),

– G is government spending (public goods and services), and

– X is net exports (exports minus imports). This method provides insights into the demand-side drivers of economic activity, essential for analyzing economic performance and policy-making in AP Macroeconomics study guides.

2.3 Income Approach

The income approach calculates GDP by summing all incomes earned by households and businesses. It is expressed as GDP = W + R + I + P, where:

– W is wages and salaries (worker compensation),

– R is rent (income from land and property),

– I is interest (income from capital), and

– P is profits (business earnings). This method highlights the distribution of income across factors of production, providing insights into economic activity and resource allocation, key for AP Macroeconomics study guides.

2.4 Economic Growth

Economic growth refers to the long-term expansion of a nation’s production capacity, typically measured by an increase in real GDP over time. It reflects improvements in productivity, technological advancements, and increased resource utilization. Sustainable growth is crucial for higher living standards and job creation. Factors influencing growth include capital accumulation, innovation, and institutional policies. AP Macroeconomics study guides emphasize understanding growth trends, drivers, and challenges to analyze economic development and stability effectively.

Business Cycle

The business cycle refers to fluctuations in economic activity, comprising expansion, peak, contraction, and trough phases. GDP tracks these cycles, measuring economic health and changes over time.

3.1 Phases of the Business Cycle

The business cycle consists of four main phases: expansion, peak, contraction, and trough. During expansion, economic activity increases, GDP rises, and employment grows. The peak marks the highest point of economic activity before a downturn. Contraction occurs when the economy slows, leading to reduced output and higher unemployment. The trough is the lowest point, where economic activity bottoms out. Understanding these phases helps analyze economic fluctuations and their impact on the overall economy, as studied in AP Macroeconomics.

3.2 Economic Indicators in Each Phase

Economic indicators vary across business cycle phases. During expansion, GDP growth and employment rise, while inflation may stabilize. At the peak, economic activity reaches its maximum, with high output and low unemployment. In contraction, indicators like retail sales and industrial production decline, signaling a slowdown. The trough is marked by the lowest economic activity, with high unemployment and reduced investment. Leading indicators, such as stock prices, predict cycle changes, while lagging indicators, like unemployment rates, confirm trends, aiding AP Macroeconomics analysis;

3.3 Role of GDP in the Business Cycle

GDP is a critical indicator in tracking the business cycle, reflecting overall economic activity and output. During expansion, GDP increases, signaling economic growth. At the peak, GDP reaches its highest point before the cycle turns downward. In contraction, GDP declines, indicating reduced economic activity. At the trough, GDP stabilizes, marking the cycle’s bottom. GDP fluctuations help identify phases, making it a key tool for analyzing economic performance and guiding policy decisions in AP Macroeconomics studies.

3.4 Factors Influencing the Business Cycle

Various factors influence the business cycle, including consumer spending, business investment, government policies, and external shocks. Consumer confidence drives spending, impacting demand. Business investment affects production and employment. Fiscal and monetary policies, such as taxation and interest rates, can stimulate or dampen economic activity. Global events, technological changes, and demographic shifts also play roles. Additionally, random events like natural disasters or political instability can cause economic fluctuations, shaping the cycle’s trajectory and impacting overall economic performance.

Inflation

Inflation is a sustained rise in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over time. It results from demand-pull or cost-push factors and monetary expansion. Causes include imbalances between aggregate demand and supply, increased production costs, or excessive money supply. Effects include reduced purchasing power, higher living costs, and economic uncertainty. Inflation is typically measured using indices like the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Understanding its causes and effects is crucial for effective economic policy-making.

4.1 Definition of Inflation

Inflation is a sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over time. It occurs when the demand for goods and services exceeds their supply, leading to higher prices. Inflation erodes purchasing power, reducing the value of money; It is measured using indices like the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which tracks price changes of a representative basket of goods and services. Understanding inflation is crucial for analyzing its economic impacts and policy implications.

4.2 Types of Inflation

Inflation is categorized into types based on its causes and characteristics. Demand-pull inflation occurs when demand exceeds supply, driving up prices. Cost-push inflation arises from increased production costs, such as higher wages or material costs, which are passed on to consumers. Built-in inflation is driven by people’s expectations of future inflation, leading to higher wages and prices. Hyperinflation is an extreme form where prices skyrocket rapidly, often due to excessive money printing, destabilizing the economy and rendering currency nearly worthless.

4.3 Measuring Inflation

Inflation is measured using tools like the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which tracks price changes in a basket of goods and services. The GDP Deflator measures price changes of all goods and services produced within an economy. Additionally, the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index is used, focusing on household spending. These indices provide insights into inflation trends, helping policymakers and economists assess economic health and make informed decisions. Accurate measurement is crucial for understanding inflation’s impact on the economy.

4.4 Effects of Inflation

Inflation impacts the economy in various ways. It can stimulate spending as individuals and businesses invest to preempt future price hikes. However, it erodes purchasing power, causing financial strain, particularly for those with fixed incomes. Inflation also introduces uncertainty for businesses, complicating long-term planning. Furthermore, it exacerbates wealth inequality as savings lose value. Addressing these impacts is vital for sustaining economic balance and stability.

Unemployment

Unemployment affects economic stability, labor markets, and consumer spending. It reflects economic health, societal well-being, and influences policy decisions and business investment strategies effectively.

5.1 Definition of Unemployment

Unemployment refers to individuals actively seeking work but unable to find employment. It is a key economic indicator measuring labor market health. The unemployment rate calculates the percentage of the labor force without jobs. Understanding unemployment is crucial for analyzing economic stability, policy-making, and societal well-being. It reflects the economy’s ability to generate jobs and maintain full employment, a primary economic goal. Accurate measurement helps policymakers address labor market challenges effectively.

- Unemployment rate = (Unemployed / Labor Force) * 100

- Importance in macroeconomic analysis and policy decisions

5.2 Types of Unemployment

Unemployment is categorized into types based on its causes and duration. Frictional unemployment arises from job transitions or information mismatches. Structural unemployment occurs due to skill mismatches or industry declines. Cyclical unemployment results from economic downturns and recessions. Each type reflects different labor market dynamics, helping policymakers target specific issues. Understanding these distinctions is vital for developing effective strategies to reduce unemployment and improve economic stability.

- Frictional: temporary job transitions

- Structural: skill or industry mismatches

- Cyclical: economic downturns

5.3 Measuring Unemployment

Unemployment is measured using the unemployment rate, calculated as the number of unemployed individuals divided by the labor force. The labor force includes those employed and actively seeking work. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) conducts monthly surveys to determine these figures. The unemployment rate provides insights into labor market conditions, helping assess economic health. Accurate measurement is crucial for policymaking and understanding economic stability;

- Unemployment Rate = (Unemployed / Labor Force) × 100

- Labor Force = Employed + Unemployed

5.4 Effects of Unemployment

Unemployment impacts individuals, families, and the broader economy. High unemployment reduces consumer spending, lowering aggregate demand and economic output. It increases poverty and income inequality, straining government budgets through higher welfare costs. Prolonged unemployment erodes job skills, reducing labor productivity. It also leads to higher debt defaults and financial instability. Societal effects include increased stress, reduced public confidence, and potential political unrest. Addressing unemployment is critical for sustaining economic growth and social stability.

- Reduces consumer spending and aggregate demand

- Increases poverty and income inequality

- Strains government budgets

Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy uses government spending and taxation to influence economic activity. It aims to stabilize output, employment, and prices, addressing economic fluctuations through targeted interventions.

6.1 Definition of Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy refers to the use of government spending and taxation to influence economic activity. It is a tool used by governments to manage economic fluctuations, stabilize output, and achieve macroeconomic goals such as full employment and price stability. By adjusting spending levels and tax rates, governments can impact aggregate demand, helping to control inflation or stimulate economic growth during recessions.

6.2 Tools of Fiscal Policy

The primary tools of fiscal policy are government spending and taxation. Governments increase or decrease spending on public goods and services to stimulate or cool down the economy. Taxation involves adjusting tax rates to influence disposable income and consumption patterns. Additionally, transfer payments, such as unemployment benefits or social security, are used to redistribute income and stabilize demand. These tools help manage economic fluctuations and achieve policy objectives like promoting growth or curbing inflation.

6.3 Effects on Aggregate Demand

Fiscal policy significantly impacts aggregate demand through government spending and taxation. Increased spending boosts demand directly, while tax cuts increase disposable income, encouraging consumption. Both actions stimulate economic activity, particularly during recessions. Conversely, spending reductions or tax hikes can reduce demand. The multiplier effect amplifies these impacts, as higher income leads to further spending. These tools are crucial for stabilizing the economy and achieving policy goals, such as promoting growth or controlling inflation.

6.4 Limitations of Fiscal Policy

Fiscal policy has several limitations, including time lags in implementation and effectiveness. Political pressures often lead to short-term focuses rather than long-term solutions. Additionally, increased government borrowing can raise interest rates, potentially crowding out private investment. The multiplier effect may also be diminished in certain economic conditions, reducing policy impact. These challenges highlight the complexity of using fiscal tools to achieve economic stability and growth effectively.

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy involves central banks using tools like interest rates and money supply to influence economic stability, aiming to control inflation and support employment through targeted interventions.

7.1 Definition of Monetary Policy

Monetary policy refers to the actions of a central bank aimed at controlling the money supply and interest rates to achieve economic goals. Central banks, like the Federal Reserve, use tools such as setting interest rates, adjusting reserve requirements, and conducting open market operations to influence inflation, employment, and overall economic stability. The primary objectives are price stability, full employment, and sustainable economic growth, ensuring a balanced and prosperous economy through careful financial regulation and oversight.

7.2 Tools of Monetary Policy

Central banks employ three primary tools to implement monetary policy: open market operations, reserve requirements, and the discount rate. Open market operations involve buying or selling government securities to control the money supply. Reserve requirements dictate the percentage of deposits banks must hold rather than lend. The discount rate is the interest rate at which banks borrow from the central bank. These tools influence interest rates, credit availability, and overall economic activity to achieve policy objectives.

7.3 Effects on the Economy

Monetary policy significantly influences economic activity by affecting interest rates and aggregate demand. Lower interest rates stimulate borrowing, increasing consumption and investment. Higher rates can curb inflation by reducing spending. Open market operations adjust the money supply, impacting economic stability. These tools help manage inflation, promote employment, and maintain economic growth, aligning with the Federal Reserve’s dual mandate to maximize employment and stabilize prices. Effective use of monetary policy fosters a balanced economic environment.

7.4 Limitations of Monetary Policy

Monetary policy faces limitations, such as time lags between implementation and effects, making it challenging to predict economic outcomes. Additionally, during deep recessions, near-zero interest rates can reduce its effectiveness, as seen in the 2008 financial crisis. Uncertainty about future economic conditions further complicates decision-making. While tools like open market operations are powerful, their impact may be diminished in extraordinary economic circumstances, highlighting the need for complementary fiscal policies to address severe downturns effectively.

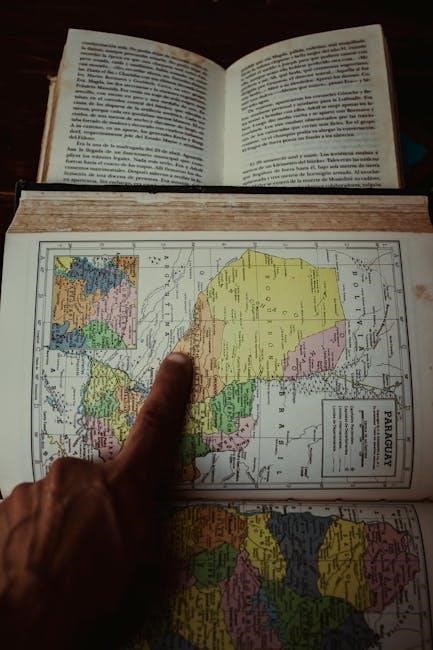

International Trade and Finance

International trade and finance explore how nations exchange goods, services, and capital, emphasizing comparative advantage, balance of payments, and exchange rates, crucial for AP Macroeconomics.

8.1 Importance of International Trade

International trade enhances economic efficiency and growth by allowing nations to specialize in producing goods where they hold a comparative advantage. This leads to lower prices, increased variety, and higher living standards. Trade fosters global economic interdependence, promoting competition and innovation. It enables countries to export surplus production and import scarce resources, balancing supply and demand. Additionally, trade agreements reduce barriers, encouraging cooperation and investment. Understanding its importance is crucial for analyzing global markets and policies in AP Macroeconomics.

8.2 Absolute vs. Comparative Advantage

Absolute advantage refers to a country’s ability to produce a good more efficiently than another. Comparative advantage, introduced by David Ricardo, focuses on opportunity costs. Even if a country has an absolute advantage in producing everything, it should specialize where it has a lower opportunity cost. For example, if Country A can produce wheat at a lower opportunity cost than cloth, it should specialize in wheat, while Country B specializes in cloth. This specialization enhances efficiency, increases production, and benefits both countries through trade.

8.3 Balance of Payments

The balance of payments (BOP) records a nation’s international transactions over a specific period. It includes the current account (trade balance, services, income, and transfers) and the financial account (investment and asset flows). A trade balance measures exports minus imports. Surpluses or deficits in the current account are offset by flows in the financial account, reflecting how nations finance their imbalances. Understanding BOP is crucial for analyzing exchange rates, trade policies, and economic stability in the global economy.

8.4 Exchange Rates

Exchange rates represent the price of one currency in terms of another, influencing international trade and investment. They are determined by supply and demand in foreign exchange markets. A strong currency makes exports more expensive and imports cheaper, while a weak currency does the opposite. Exchange rates are affected by inflation, interest rates, and economic stability. Understanding exchange rates is vital for analyzing trade balances, foreign investment, and global economic interactions, making them a key topic in AP Macroeconomics study guides.